What is a concentrated stock position?

If one stock makes up more than 10% of your overall asset allocation, it’s probably too much. A diversified portfolio is the cornerstone of a risk-adjusted investment strategy. Since single stocks don’t move like the broader market, you’re exposed to much greater risk.

Whether you inherited a concentrated stock position or have company stock as an employee or founder, the result is generally the same. Unfortunately, most executives and insiders have less flexibility to reduce risk on a concentrated position of company stock.

The situational nature of planning to diversify one large position cannot be over-emphasized, so it’s important to work with a financial advisor who has experience in this area. So if you have a large portion of your wealth tied to a single stock, here are six options to manage it.

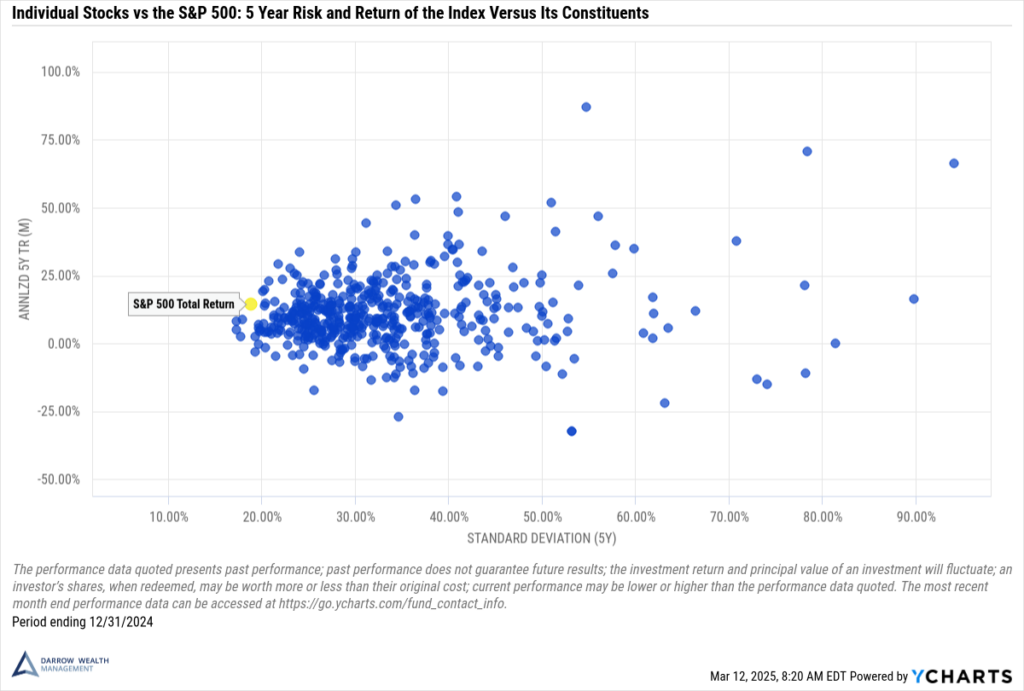

Individual stocks vs the stock market

Just because a stock is in the S&P 500 doesn’t mean it moves like the index. Over the most recent five year period ending in 2024, here’s the annualized returns and volatility of the 505 companies in the S&P 500 versus the index itself.

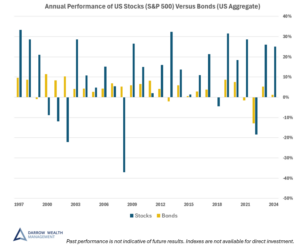

Historically, on average, the S&P 500 has produced positive calendar-year returns 75% of the time. But that’s across the largest 500 public companies – not just one. There’s a significant amount of dispersion within that. Of course, there’s the potential for much greater upside, but emphasis is on the potential.

If you’re feeling unsure about reducing your exposure to one stock, consider these statistics about returns and volatility:

- How many single stocks outperform the market? Between 1987 and April 2024, roughly 67% of individual stocks underperformed the Russell 3000. Of the underperformers, 39% actually lost money. (BlackRock)

- Big losses in single stocks are common. Between 1980 and 2020, nearly 45% of all companies that were ever in the Russell 3000 experienced a 70% drop in stock price from the peak and never recovered. When considering the distribution of excess lifetime returns of individual stocks vs the Russell 3000, the median stock underperformance was almost -10%.(J.P. Morgan Private Bank)

6 ways to manage a concentrated stock position

In no particular order, here are some strategies to reduce the risk of concentrated stock holdings. Although all these approaches won’t be right for all investors, often it’s advantageous to consider multiple strategies to diversify.

- Options Contracts: Utilizing options like cashless collars, covered calls, and protective puts to manage risk or generate income.

- Outright Sales: Selling stock through market or limit orders.

- Diversifying Around It: Balancing the portfolio by investing in assets that offset the concentrated position’s risk.

- Exchange Funds: Contributing shares to a private fund in exchange for a diversified basket of equities after seven years.

- Charitable Contributions: Donating appreciated stock to charity while reducing capital gains tax.

- Gifting: Transferring stock to family members or trusts.

Options contracts as income and hedging strategies

Options are often used in various hedging strategies, including single stock risk management strategies. In the right situations, investors can use options trading strategies to diversify, reduce risk, or generate income from a large stock holding. Here are a few simple examples depending on the goals.

Cashless collar

Can help with: capping downside risk using income from options premiums (cost-neutral)

With a cashless collar, an investor sells a call option on a stock they own then buys a put option with the proceeds. When you sell a covered call, you sell someone the right to buy the stock from you at a specific (higher) price for a certain period of time. In turn, you’d buy a put, which is the right to sell someone the stock at a specific (lower) price for a certain period of time. As with anything, there are pros, cons, and limitations.

In practice, it can be hard to get cash neutral offsetting positions as investors generally seek to maximize upside and get also achieve maximum downside protection.

Sell a covered call option

Can help with: income and liquidity with the potential to trim your concentrated position

Selling options contracts is explained in the first leg of the above example. Whether or not the option is called at expiration, you keep the option premium. Again, trading options has risks and drawbacks. Here, it’s most notably the lack of downside protection. Options are priced on volatility and the premiums aren’t always worth it.

Buy a protective put

Can help with: downside protection on some of your stock

Purchasing puts is explained in the initial example. This approach could be attractive to investors who aren’t looking to sell a large position but want some price protection on a portion of their shares. However, there are drawbacks of going this route: it doesn’t help diversify a single stock position and means using other diversified or liquid assets to fund the put option purchase, essentially furthering your concentration.

Ultimately, weigh the merits of a put-only approach. Consider whether the cost of the put option is worthwhile when you could just sell the stock today at a higher price.

Other considerations on options trading

There isn’t an options market for every stock. Stocks with a smaller market cap or newly public companies might not have any takers. Given the options terms, this is usually best as a shorter-term strategy. Executives and current employees with company stock usually have trading rules that preclude them from using any hedging strategies such as this. Finally, options are complex instruments. Work with a wealth advisor to discuss your financial goals and individual risk tolerances.

Outright sales

Though this option is obvious, that doesn’t mean it’s without merit. Taking profits is a key part of managing concentrated stock positions. Investors can place a market order to sell stock right away or enter limit orders. A limit order becomes a market order if the stock price reaches a preset level. Always consider trading volumes before putting up an order.

Managing concentrated stock by diversifying around it

Diversifying concentrated stock positions can involve multiple approaches. Right-sizing a concentrated position ultimately requires divesting or selling stock in some form, but there are ways to gain more balanced exposure to the broader market by other means.

To illustrate, consider the following simple hypothetical examples.

Your concentrated position is a large technology stock, currently occupying 30% of your portfolio. The rest of your portfolio is 40% in an S&P 500 fund and 30% bonds. In March 2025, the technology sector is roughly 31% of the S&P 500 index. On a weighted average, your portfolio would be 42% technology.

This issue is further compounded when the concentrated position is one of the largest companies in the US market. Following on the example above, if the large holding was 5% of the S&P 500, the diversified portfolio ends up adding another 2% to the concentrated position. In all, compared to the whole stock market, you’d have an 11% sector overweight and 27% more exposure to the company stock.

When considering concentrated stock strategies, one way to reduce unnecessary market risk is avoiding areas of the market you’re already over-exposed to. This includes the stock itself, its sector, industry, and other highly correlated assets.

Direct indexing and other strategies

Solutions can be achieved through custom asset allocations and targeted investment strategies, such as direct indexing, aggressive screening of ETFs, etc. With these approaches, the goal is avoiding the areas of the market you’re already concentrated in and overweighting the rest. So when taken as a whole, the entire portfolio is more aligned with the broader market. Discuss your situation with an investment adviser.

Exchange funds

At a high level, with an exchange fund (sometimes called a swap fund), individuals contribute stock to a private fund in exchange for ownership in the fund. The goal is to create a diversified basket of stocks through everyone’s individual contributed holdings. After seven years, investors can exit the fund with a more diversified mix of equities.

A complete discussion of the pros and cons and workings of swap funds is outside the scope of this article, but there are many things to consider before investing. But if you’re looking to reduce capital gains tax, this strategy won’t help. Exchange funds don’t change the investor’s original cost basis from the contributed shares.

Charitable contributions

If you have charitable goals, your concentrated stock position may be a great vehicle to be generous to your causes and reduce your income tax bill. By donating highly-appreciated securities instead of cash with a donor-advised fund you may be able to take a tax deduction for the fair market value of the asset, up to 30% of adjusted gross income (AGI) if you itemize.

You may be able to maximize the tax benefits of a donor-advised fund alongside a large sale of stock, though there is a five-year carry forward for unused deductions.

Gifting stock to family outright or in trust

Depending on your financial situation, you might not even need the proceeds from a large holding. In this case, you can speak with your estate planning attorney about gifting stock to family outright during your life (perhaps someone in a lower tax bracket!) or putting shares in trust to maintain some control while removing the value from your estate.

This strategy is riddled with potential tax consequences as well as tax and estate planning opportunities.

Capital gains tax considerations

Most investors delay diversifying because of tax implications. Founders and early investors often have super low basis stock to the point where virtually the entire gain is taxable. Taxes should always be a component of any investment decision — but not the main driver. With so many nuances in the tax system, always consult your tax and financial advisor before taking action.

Ways to reduce capital gains tax from a concentrated position:

- Individuals who inherit a concentrated stock position should speak with their estate planning attorney to confirm if they’ll get a step-up in basis. If so, there might not be any material capital gains tax impact from selling shares.

- For company founders and early employees, find out if the stock is qualified small business stock under Section 1202 and can potentially be sold tax-free.

- Tax-loss harvesting to offset capital gains taxes from sales. Learn more about the pros and cons of harvesting losses.

- Moving to a state without income taxes before realizing gains. Speak with your tax advisor to confirm gains cannot be sourced (and taxable) to your former state.

Concentrated stock strategies

Whether you opt for complex solutions like exchange funds or direct indexing strategies or go for the simplest approaches of selling stock in market or limit orders, in most cases, unwinding a concentrated single stock position takes some time. So if you know the risks, don’t delay taking action, especially if your hesitancy is driven by taxes. Protect your gains (even if they’re taxable) by diversifying and taking profits.

Schedule a consultation with a wealth advisor to discuss how we may be able to help you unwind a concentrated holding.

This is a general communication for informational and educational purposes only and not to be misinterpreted as personalized advice or a recommendation for any specific investment product, strategy, or financial decision. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products. If you have questions about your personal financial situation, consider speaking with a financial advisor.

[Last reviewed March 2025]