Tax-loss harvesting is the process of selling an investment that has lost value in your portfolio to ‘realize’ the loss for tax purposes. Investors can use this loss to offset taxable capital gains and potentially reduce ordinary income by up to $3,000 for the year. The remainder can be carried forward as a deduction in future years. Is tax-loss harvesting a good idea? Before putting this tax strategy into action consider whether the savings are worth the risk.

How tax-loss harvesting works

Investment losses can reduce gains. For investors with significant taxable gains from investment activity, it may make sense to consider tax-loss harvesting.

By selling at a loss, you may be able to offset your capital gains, and save money on taxes. A net loss for the year can reduce regular income up to $3,000 (or $1,500 for married filing separately). Any remaining losses over this limit can be carried forward to future years.

Example of tax-loss harvesting:

Olivia has $50,000 in short-term capital gains due to stock sales. Olivia currently doesn’t have any other gains or losses for the year. In her account, she has other holdings including 200 shares of BigBet company, which she purchased this year for $80/share. BigBet is now trading at $20/share. If Olivia decided to sell her shares of BigBet, she could generate an ($12,000) loss (($20 – $80) * 200). This would bring her short-term gain for the year down to $38,000.

Short-term assets are taxed at higher ordinary income rates. Therefore, tax-loss harvesting is most advantageous when you can wipe out short-term gains. Note that short-term capital gains distributions from mutual funds are considered ordinary income and cannot be reduced by capital losses.

Wash-sale rules

Wash-sale rules are one of the most important parts of tax-loss harvesting to be aware of. Under the wash-sale rule, if you buy an identical or substantially identical asset within 30-days (before or after) selling for a loss, the loss isn’t allowable. The wash-sale rules are in place to prevent taxpayers from selling an asset just for tax benefits.

The IRS doesn’t provide explicit definitions as to what is “substantially identical.” However, investors should be aware that broad-based ETFs and mutual funds as or single stocks can violate the wash-sale rules. For example, if you have an iShares S&P 500 ETF and want to sell it for a loss and buy Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF, it would be considered a “substantially identical” transaction and disallowed loss under the wash-sale rules. Your financial institution tracks this information.

This is important for investors to know when considering selling an asset that fits into long-term investment goals that may not be easily replaceable within the parameters of wash-sale rules.

Is tax-loss harvesting a good idea? How to tell if it’s worth it

Tax-loss harvesting is worth considering annually based on your tax and financial situation for the year. Like most financial and tax strategies, it is not appropriate for everyone or even every year so it’s important to weigh the pros and cons and stay focused on your specific situation.

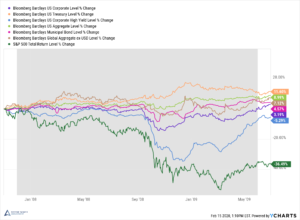

Using asset location to reduce tax

As you consider ways to reduce your overall tax, review how efficient your asset location is. By holding tax-efficient investments in taxable accounts, you can keep more tax-inefficient funds in tax-deferred retirement accounts and avoid paying tax annually until the funds are withdrawn (withdrawals from a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k) are tax-free if you’re at least 59 1/2 and at least 5 years have passed since the first Roth contribution was made).

Harvesting losses for tax reasons alone can backfire

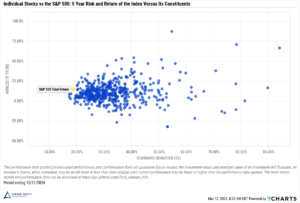

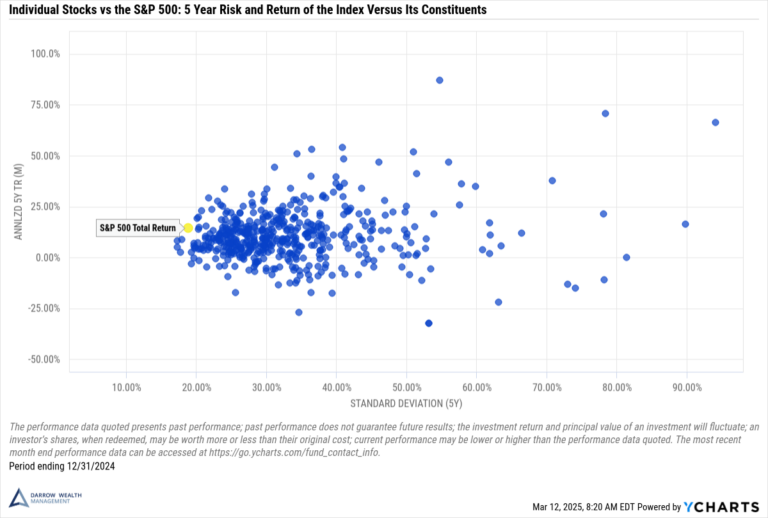

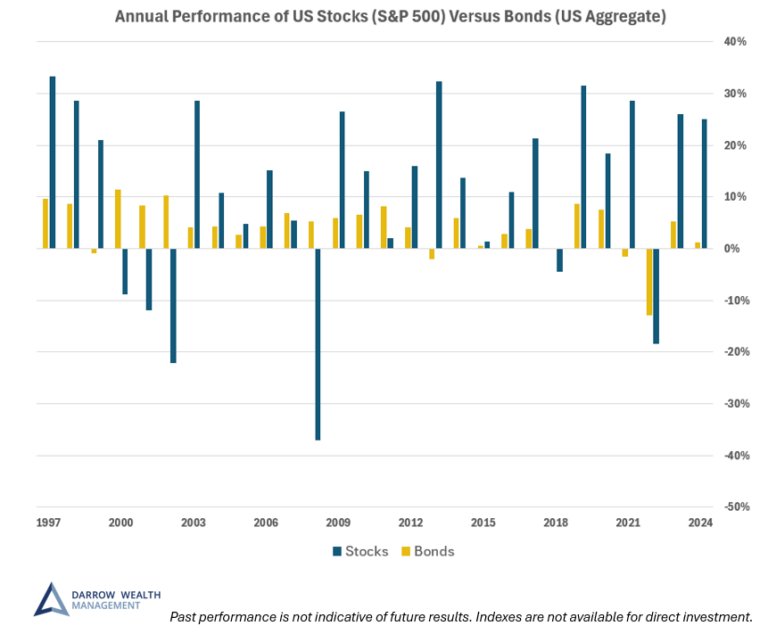

For investors with a well-diversified investment strategy and a buy-and-hold investment philosophy, tax-loss harvesting may not fit in. Asset class diversification is a great way to reduce investment risk by maintaining adequate exposure to a number of different asset classes. If one of the asset classes is performing poorly in a given year, is it worth the risk to sell your positions to take the loss for tax reasons, knowing that you’ll be off of your investment target for at least 30 days?

The markets can change on a dime: between January 2002 and December 2021, 70% of the best days for the S&P 500 occurred within 2 weeks of the worst days.

Recent history also exemplifies the potential hazards of tax-loss harvesting:

In June 2022, the S&P 500 lost -7.57% including dividends. Seemed like a great time to harvest losses, right? The index went on to return 8.08% in the month of July. For the diversified investor looking to maintain a particular asset allocation, perhaps not.

Tax-loss harvesting to diversify out of a concentrated stock position

Unlike the last example, where losses were being harvested solely for tax savings, if an investor is looking to make asset allocation changes anyways, tax-loss harvesting may be a good idea.

As previously discussed, one situation where this tax strategy could be employed is when an investor is looking to diversify out of a concentrated stock position with significant gains and has a corresponding single-stock holding with losses.

Employees with stock options and equity compensation are often in this situation, even with stock from the same company. Early grants with a low strike price or cost basis can appreciate significantly, but as your tenure with the company continues, later grants or awards could lose value relative to the price you paid for the stock or your cost basis at vesting. Since the goal is to diversify out of the stock not purchase more, the wash-sale rules don’t pose an issue.

Making withdrawals from taxable accounts

Another situation where tax-loss harvesting can be advantageous is when you need to take out funds from your brokerage account. Rather than only sell positions with gains, look at your realized gains and losses for the year. Consider how you could structure your withdrawal to offset gains without disrupting your ideal asset allocation too much.

As part of periodic rebalancing

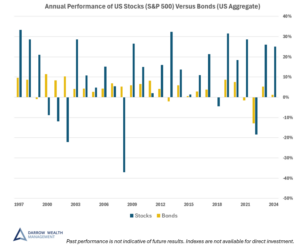

Your asset allocation (the percentage of your account that you distribute between different asset classes, such as bonds, real estate, or U.S. equity) will typically change each year, as funds representing an asset class outperforms or underperforms relative to other funds. Even one asset class can move from being a top performer one year to the bottom the next.

Without periodic rebalancing, this can distort your portfolio, leaving you invested more aggressively – or conservatively – than you expect. Rebalancing is the process of selling out-performing funds and reinvesting the proceeds in other positions to align your current asset allocation with the original.

Since the market will always move, it doesn’t make sense to rebalance negligible variations. There are other considerations too, but during this process it’s a good time to think about tax-loss harvesting.

Recap on the tax treatment of brokerage accounts

When you sell a stock, bond, mutual fund or ETF, you can trigger a taxable capital gain or loss depending on how your gains and losses net out at the end of the year. Note that when you invest using a taxable investment account (also called a brokerage account), you may owe tax annually even if you do not sell any of your holdings, as some dividends, interest, and capital gains distributions from mutual funds (and some ETFs) are taxable, whether paid out or reinvested.

For tax-loss harvesting to be worth it, you’ll first need to calculate realized taxable gains and losses for the year. You do this by netting gains and losses.

The process for netting capital gains first applies to gains and losses of the same holding period: long-term gains and losses are netted against each other, and separately, short-term gains are used to offset short-term losses. If the resulting short-term and long-term figures involve a gain and a loss, they are netted once more. In general, a long-term holding period applies to assets held for at least one year and one day. Assets held for a year or less are short-term for tax purposes.

Example:

Short-term calculation

ABC Stock = $40

XYZ Stock = ($50)

Total short-term loss = ($10)

Long-term calculation

DFG Bond = $5

HIJ Stock = $10

Total long-term gain = $15

The short-term loss ($10) is then offset by the long-term gain $15 to result in a long-term gain of $5. Had the long-term figure above been a loss instead of a gain, the taxpayer would have had both a short and a long-term loss.

Note that this is a highly simplified example. On your tax return, gains and losses from all asset types are included in the calculation, not just stocks and bonds.

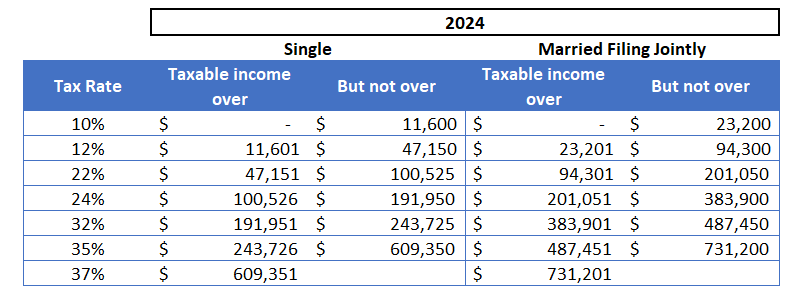

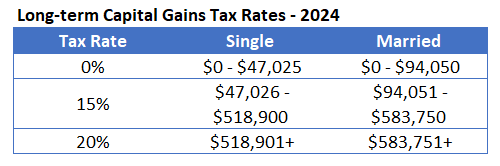

2024 tax brackets for income and capital gains

Due to the 3.8% net investment income tax (NIIT), the actual tax rate for regular income and short-term capital gains could be as high as 40.8%. The long-term capital gains tax rate can be as high as 23.8%. These figures are only for federal tax, so your total tax rate could be even higher with state taxes. The NIIT applies to the lesser of net investment income or the amount by which modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds $250,000 for couples filing jointly, and $200,000 for single filers in 2024.

Any time you make changes to your portfolio, you’ll want to consider trading costs and transaction fees in the equation. Like any tax strategy, the benefits and considerations will vary over time as tax laws and your financial situation change. Speak with your financial advisor and CPA before making any changes to help ensure you’re not letting the tax-tail wag the dog.

This is a general communication should not be used as the basis for making any type of tax, financial, legal, or investment decision. Discuss your situation with your personal tax advisor.

Last reviewed February 2024