Stock options or awards can be quite complex. But it’s important to understand how stock options work, especially if it’s a big part of your compensation. The goal of this article is to provide employees with a complete primer to their stock options. Employer stock may be a significant part of your net worth, which is why it’s so important to partner with professionals who can help you make the right decisions for your individual situation and goals.

How do stock options work?

To maximize the benefit of stock options or awards, you’ll need to have an integrated strategy that can help you diversify your investments, while taking into account the tax implications and other financial planning considerations.

TLDR (the takeaway): We specialize in working with employees who have stock options. If stock options are a large part of your compensation, consider working with a wealth advisor who specializes in the space. Learn more about our services.

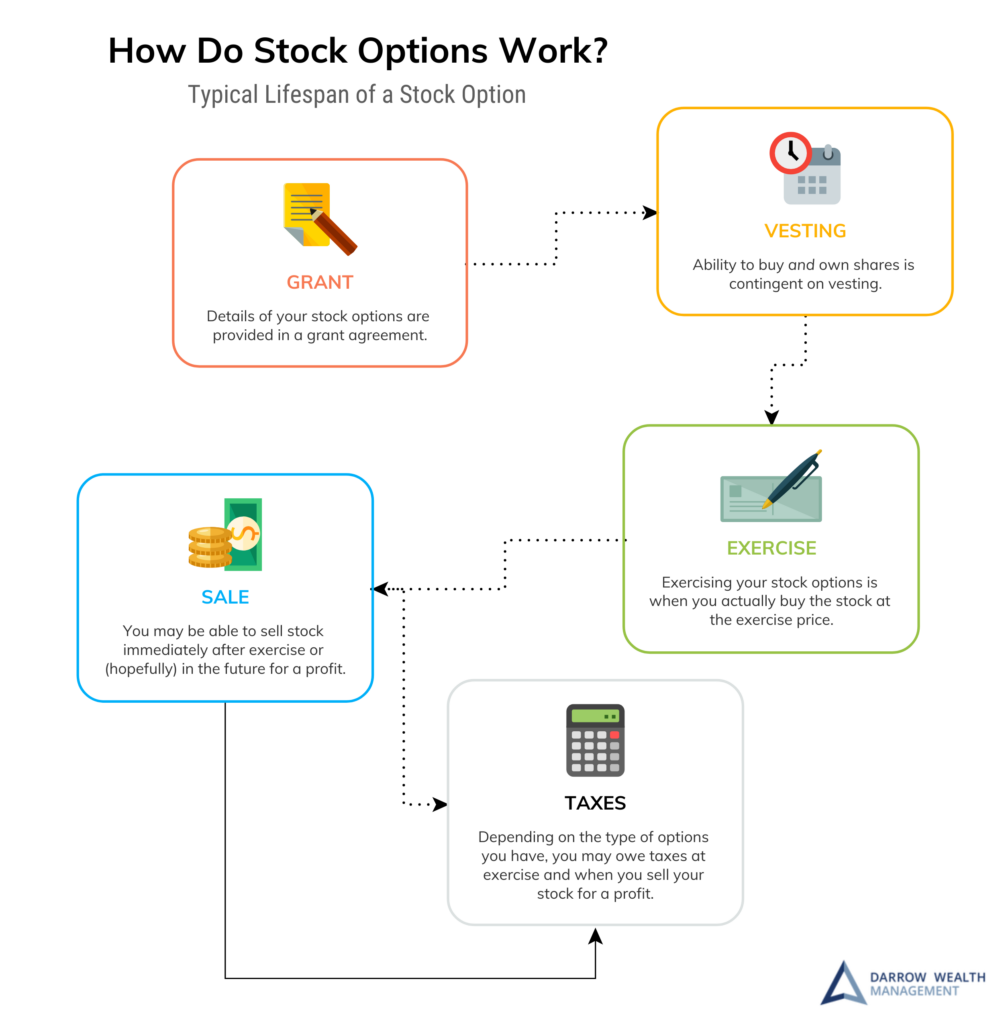

Life span of a stock option

- Grant. The stock option is born! The company grants you the right to buy __ number of shares at $__ price/share (exercise price) beginning at __ date and expiring on __ date. Your grant document will fill in the blanks.

- Vesting/exercise date. Usually, you can first exercise stock options when the shares begin to vest. However, some startups will allow the early exercise of unvested stock options. If you leave the company before the shares vest, you lose the right to exercise the option, as you never earned the right to begin with.

- Exercise (potentially). When/if you decide to exercise, you’ll pay the strike price * number of shares to buy the stock. At private companies and startups, you’ll generally need to come up with the cash to buy the stock (and possibly cover tax too). If you’re working for a public company, you’ll probably have the option to do a cashless or net exercise. The exercise date is important; it sets the holding period for your shares, your cost basis, and cements your status as a shareholder.

- Sale (potentially). If you exercise your stock options, you may decide to do a same-day sale or hold the stock. You usually, but not always, have the ability to control the timing of the sale. For example, if your employer is acquired you likely won’t have a say about what happens to your stock.

- Expiration. Employees who stay with the company usually have 10 years from the grant date to exercise the option. If you let an option expire, even if it’s in-the-money (current price > exercise price), the option holder will get nothing. Typically, if you leave the company, you’ll have a much shorter time frame to exercise (90 days is common).

Key employee stock option terminology

Throughout this article we will be using a number of terms to explain how stock options and equity awards work:

- Exercise price (or the strike price). The exercise price is the price you’re able to buy the shares. This price is set in advance and doesn’t change.

- Fair market value (or FMV). Fair market value is the price of a share of company stock in the open market. If publicly traded, the price on a public stock exchange is the FMV. If the company is private, the company will value the shares, called a 409a, usually at least once a year.

- In-the-money. When a stock option is “in-the-money” or “above water” the strike price is less than the fair market value of the shares. Here’s an example: if your exercise price is $5 and the stock is trading for $10, it’s “in-the-money.”

- Out-of-the-money. When a stock option is “out-of-the-money” or “underwater,” the strike price is more than the fair market value of the shares. Using the previous example, if the stock was trading for $4 not $10, it would be “underwater”.

- Cashless exercise. Usually only available at public companies, this is a same-day exercise and sale of your stock options. A portion of the proceeds will be used to cover the cost of buying the stock and possibly tax withholding. You’ll receive the net cash proceeds.

- Net exercise. Usually only available at public companies, a net exercise is when you exercise the shares and some shares are held back to cover the cost of buying the stock and potentially tax withholding also. You receive the net shares to hold.

The basics of how stock options work

Employees who have stock options are granted the option to buy company stock at a set price – the strike price – and on or after a certain date, typically the vesting date. When you buy the stock at the strike price, you’re exercising your stock options, and you then own the shares. (Note, in some plans, it’s possible to early exercise stock options, which means buying the shares before they vest).

Stock options are granted at current value of the stock at that time. As the stock (hopefully) appreciates, you’ll have the ability to buy the shares at the exercise/strike price, instead of paying the current value. Options that are vested and not underwater (e.g. the strike price is greater than the current value of the shares) cannot be cancelled without some type of compensation.

Typically, the option to exercise is open for 10 years from grant. So at vesting, you’ll have the right but not the obligation to exercise this option. It’s your responsibility to make sure you don’t accidentally let in-the-money stock options expire! But before exercising, understand the tax implications.

With stock options, it’s pretty easy to find out when you can exercise and buy the shares. But if you work for a private company, you may not have clarity on when you’ll be able to sell. This can create liquidity, tax, and concentration issues.

What type of employee stock options do you have?

Companies grant two kinds of stock options:

- Nonqualified Stock Options (NQSOs) are the most common type of stock option. When you exercise in-the-money stock options, the difference between the exercise price and the market value is going to be taxable W-2 income to you, at ordinary income tax levels plus Social Security and Medicare taxes.

- Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) offer tax benefits: after you exercise the options, if you hold the stock for at least two years from the date of grant and one year from the date of exercise, you receive favorable long-term capital gains tax treatment for all appreciation over the exercise price. But caution! Don’t overlook the significant tax impact that ISO exercises and sales may have upon calculations of alternative minimum tax (AMT); failure to plan for this can result in a shock come tax-time.

When to Exercise Stock Options

Restricted stock units (RSUs) aren’t stock options – they’re equity awards

The difference isn’t just semantics either. Unlike stock options – which require the employee to purchase the option at the strike price – restricted stock units are just given to employees as equity awards, typically upon vesting. So unlike stock options which can become “underwater” if the market price is less than your purchase price, RSUs always have some value unless the stock goes to zero. Obviously, at that point, you would have other issues to contend with.

At grant, RSUs have no tax or income implications as they are not yet earned. To earn the shares, employees must vest. Many public companies will require time-based vesting but could also include other performance-related requirements, like reaching a target stock price.

Private companies typically have a time-based vesting requirement in conjunction with an event-based requirement, such as an IPO, funding, or an acquisition for liquidity. When RSUs vest they become common stock. The value of your equity grant is determined by the market value on the vesting date.

Restricted stock awards (RSAs) are another common type of equity-based compensation

A restricted stock award is a type of stock compensation plan where employees or executives are granted (or may purchase) a specified number of shares of company stock (or cash equivalent) to be received at a later date, after vesting requirements are met.

For restricted stock awards to yield any value, employees must first satisfy the vesting requirements, which may be time or performance based. RSAs allow employees to make a choice about when to pay income tax on the award – called an 83(b) tax election. Although very similar to restricted stock units, restricted stock awards are not the same thing.

How are stock options taxed?

The tax treatment depends on what type of stock options you have. Incentive stock options (sometimes qualified stock options) can have tax benefits if holding periods are met. Non-qualified stock options do not.

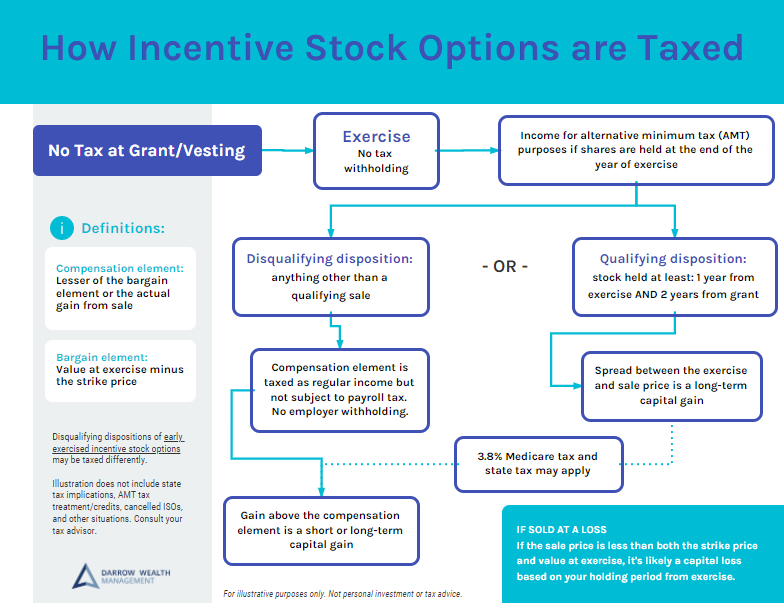

Tax treatment of incentive stock options (ISOs)

As mentioned earlier, holding ISOs through the end of the calendar year in which you exercised the options can often trigger the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Further, your employer won’t withhold any amount at exercise or sale to cover your potential income tax liability.

So although incentive stock options do have tax benefits if you satisfy the holding period requirements (at least two years from the date of grant and one year from the date of exercise), in many situations it still may not be advantageous to do so. The AMT and the risk the options may become underwater are two driving factors. This infographic has more on the taxation of incentive stock options.

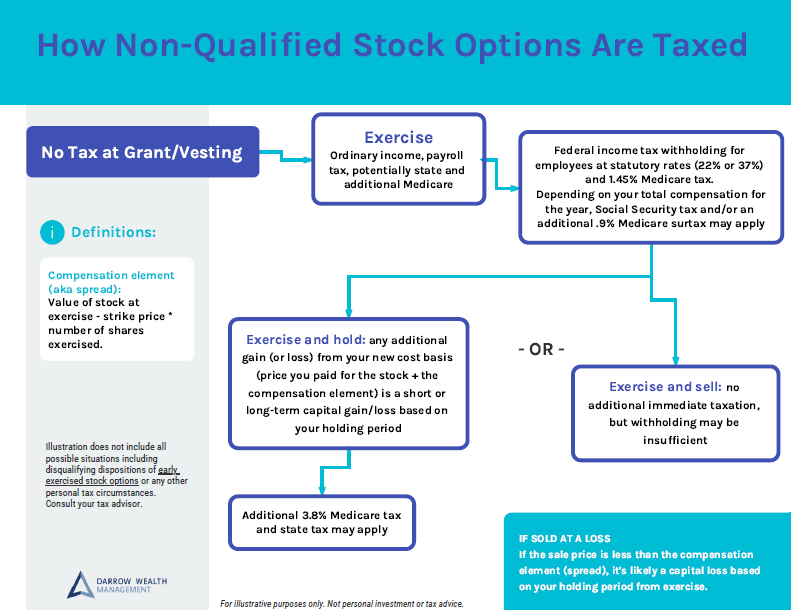

Taxation of non-qualified stock options (NQSOs)

Generally, federal tax withholding at exercise is required. If the spread is under $1M, the rate is 22%, if above, it’s 37% – this is set to increase in 2026. If your state has an income tax, withholding is likely required too. The compensation element is also subject to payroll taxes. The statutory withholding may not be enough to cover your tax liability. Further, there may not be withholding for individuals who were/are not classified as employees, such as independent contractors or consultants.

Assuming they are not underwater, non-qualified stock options will be taxed at both ordinary income rates and either short-term or long-term capital gains tax rates. This infographic has more on the taxation of non-qualified stock options.

Tax treatment of restricted stock units (RSUs)

When vesting occurs for U.S. employees, the value of the stock grant is ordinary income for tax purposes. Ordinary income (or W-2 income) is subject to federal, state, and local taxes in addition to Medicare and Social Security (up to the maximum; $168,600 in 2024).

Although many employers will automatically withhold a portion of income to cover some of the tax due some additional tax planning may be required, as the amount may not be sufficient depending on your situation. It is advisable to consider consulting a CPA or other tax professional to determine whether a quarterly tax payment is required to avoid underfunding your tax liability.

Taxation of restricted stock

The tax treatment of restricted stock awards is one of the more unique features of this type of equity compensation. Individuals have some say in how their RSA is taxed through the choice to either make an 83(b) tax election or take no action and proceed with the default tax method.

Default taxation of restricted stock awards

No tax is due at grant. At vesting, the difference between the fair market value and the amount you paid for the shares is ordinary income. If you sell the shares immediately, there are no other tax consequences. If you hold the stock, any further gain or loss after vesting is considered a capital gain or loss when you sell the shares.

Whether you’ll have a taxable capital gain or loss depends on your holding period. More than one year is long-term, anything less is short-term. Short-term capital gains rates are essentially the same as regular income.

83(b) tax election

An 83(b) tax election allows restricted stock award recipients to pay ordinary income tax on the award before it vests. The portion of ordinary income is the difference between the fair market value of the stock at grant and what you pay for the shares. Any additional gain or loss after the shares vest is a long-term capital gain or loss. You’ll pay the tax in the year you sell the stock. This article has more on restricted stock.

Other ways employees own company stock

- Employee stock purchase plan (ESPP): Section 423 employee stock purchase plans allow you to buy shares, typically at a reduction of 5% to 15% compared to the market price. ESPP accounts will withhold a portion of pay through regular payroll deductions, up to $25,000 per year. The ESPP plan buys the stock a few times a year, semi-annually or quarterly usually.

- Employer stock in your retirement plan: According to Bloomberg’s ranking of retirement plans, in 2014, one in five of the largest companies in the S&P 500 made 401(k) contributions in company stock. Owning too much company stock in always a risk. But when the shares are in your retirement plan, it can have devastating effects. While you can’t control whether your employer matches in cash or stock, you can control the asset allocation for your contributions. In the right situations though, there can be tax benefits to holding company stock in your 401(k): net unrealized appreciation.

Can you have too much company stock?

In a word: yes. And most people do. How much you should invest in employee stock options and company stock depends on your assets and risk tolerance. In general, don’t tie up more than 10% of your net worth in your employer’s stock.

Owning too much of any one company is a risk; and it is a risk that many investors actually choose to take, whether they intend to or not. This article has more on why putting too many eggs in one basket and over-investing in company stock can be a bad idea.

Managing concentrated stock positions and how to diversify

How to diversify out of a concentrated stock position depends on your individual situation. But in general terms, there are several ways employees can reduce their concentration in employer stock:

- If your compensation package is too heavily weighted in stock options or restricted stock units, try to renegotiate. Perhaps you can restructure a deal that is more balanced.

- If your employer matches retirement plan contributions in shares of company stock, you may be able to diversify right away. Most companies who match only in employer stock allow sales immediately. Read your retirement plan documents for more information.

- If you’re receiving stock options or RSUs, you may reconsider participating in an employee stock purchase plan. You can’t control your grants, but buying shares in an ESPP is optional.

- If your company stock is a big part of your compensation and net worth, consider working with a financial advisor and CPA to develop a plan to systematically liquidate and diversify your positions. This doesn’t always mean selling everything, either. By developing a systematic diversification strategy integrated with your entire financial life, you can help ensure you’re making the most of your stock options. Advisors can help keep an eye on potential tax consequences and your overall risk exposure.

6 Ways to Diversify a Concentrated Stock Holding

If you quit, retire, are fired, are laid off, or otherwise leave the company

One of the difficulties in understanding how stock options work is all the event-based factors that can change the situation. Several factors impact whether you can keep your stock options, RSUs, or other stock compensation after changing jobs. It may be a surprise that the reason for your departure can impact the outcome for your stock.

Other key factors include:

- Whether your shares are vested and whether or not you’ve exercised

- What type of equity compensation you have? (e.g. stock options, restricted stock units, employee stock purchase plan, stock appreciation rights, phantom stock)

- Whether your employer is public or private – or a public company that later goes private

- Why you’re leaving the company (retirement, a new job, laid off, terminated with/without cause)

- What (if any) specific terms you negotiated with the company

Termination for cause will typically result in cancelling vested or unvested options that haven’t been exercised. But if you leave for another reason, you may still be able to exercise your vested options. In most plans, RSUs, and stock appreciation rights (SARs) shares of stock or settled in cash upon vesting.

If you leave before vesting, you will likely lose your equity compensation. This article has more on what happens to your stock options when you leave the company.

What happens to employee stock options after an IPO?

Do you have stock in a private company planning to go public? Pre-IPO companies use valuation experts to value the stock. The company needs a system in place for employees to sell their shares. If your company is planning on going public in the near future, this can be both good and bad news.

Going Public via SPAC Merger or Direct Listing

An IPO is good because you will (eventually) be able to sell your shares after exercise on a public exchange. Going public could add new risk because of the lockup period. After the IPO, insiders like employees can’t sell their shares right away. The lockup period usually ranges from 90 to 180 days.

What may happen after your company goes public will depend on a number of factors, such as whether you have stock options or restricted stock units at a pre-IPO company. Not all IPOs are successful. Sometimes, they never even get off the ground. Learn what can happen to your stock options after a failed IPO.

What it means for your stock options if your company is acquired

Unfortunately, there is really no concrete answer for this question. What can happen will be determined by a number of factors: for example, are your options vested or unvested? Have you exercised the options? Is your company public? Is your company selling to a private firm?

You will probably have to wait until the terms of the M&A agreement are released, but in the interim, read your stock option agreement. There should be some language in there about what may happen in the event of a merger or acquisition. More in this article on what happens to stock options after a company is sold or merges.

What happens to restricted stock units or awards after an acquisition?

What can happen to restricted stock units after a company sells or merges will depend on several factors. It isn’t always about money either. If the acquiring firm doesn’t give current employees stock options, it may not want to. The terms of the deal play a large role too. Is your company is being sold in an all cash deal, all stock, or blend of the two?

Financial advisor for employees with stock options

Darrow Wealth Management specializes in working with employees who have stock options. Through our ongoing advisory relationship, we can help you make a plan to exercise, diversify, and allocate the proceeds to your other financial goals. There’s a lot that can happen when you have equity compensation. No two situations are exactly alike. If stock options are a large part of your compensation, consider working with a wealth advisor who specializes in the space. Learn more.

[Last reviewed February 2024]